Mathematics was and is a tool, and so is AI

Earlier today, I picked up my business cards for a new venture ChurnShift Inc. and on my walk home, I passed a controversial billboard clearly designed to provoke and rattle people. As someone trying to sell a new useful human-in-the-loop AI tool, I found it impossible to ignore. So maybe kudos to the ad agency, who I bet were a group of human psychologists turned into advertisers. And maybe not kudos, because it is very low to create fear and bank on it. This billboard sparked a reflection that led to this blog. Here I am trying to cut through the hype, dispel myths, and clarify facts and simply give my opinion so that our prospects and investors understand where we stand regarding AI, and moreover what we mean by AI and AGI in comparison to others in this crowded and confusing space.

What is AI anyway?

When I started in grad school at the Computational Linguistics group of University of Toronto, I was bewildered, confused, and scared. I was walking among all the big names in the field, and their colliding ideas and philosophies. I too wondered "What is AI anyway?", a subject that I am supposed to write a thesis in one area of it.

So I told myself, before trying to write about AI or build an artificial version of intelligence, I need to understand the natural/human form of it. I could go and read what Marvin Minsky meant by it, but I need to understand it myself.

So what is intelligence? – and specifically human intelligence?

I am still refining and learning the multi-faceted meaning of intelligence as I grow older and experience life at different stages. Yet back then, since I was working on a subject that dealt with type hierarchies and how they are used in natural language grammar design systems, I settled on the following definition for my thesis. I found this definition on Wikipedia, and it was so intriguing that later on I found the actual book from the 1930s : “Great Philosophies of the World” by C.E.M. Joad.

"The intellect, then, is a purely practical faculty, which has evolved for the purposes of action. What it does is to take the ceaseless, living flow of which the universe is composed and to make cuts across it, inserting artificial stops or gaps in what is really a continuous and indivisible process. The effect of these stops or gaps is to produce the impression of a world of apparently solid objects. These have no existence as separate objects in reality; they are, as it were, the design or pattern which our intellects have impressed on reality to serve our purposes."

There is so much to understand and unpack here, but in this post I only focus on these concepts:

The intellect evolved for the purposes of action and is a purely practical faculty.

Of course this definition does not capture all aspects of human intelligence. There are some utilitarianism in this definition that might be construed as unethical, and not everything that we do or should do must be a means to an end. So this definition is part of what we should consider intellect but not all of it.

At this stage of my life, I see kindness and living with the rhythm of nature as true intelligence. And if that is our purposes of action then we need to act and come up with practical ways of achieving that.

In the following, I am only focusing on one aspect of intelligence that arises from our economical behavior.

Mathematics as a toolbox

Some people assume that if you know math or you are good at math, you are intelligent. But math itself is a practical tool that we have invented to serve our purposes and for practical reasons - like any other tool. A hammer, a shovel, a set of wheels, etc. are physical tools that we invented because they served a practical purpose for us. The same is true for abstract tools that we find and continue to invent in our mathematical toolbox.

But how was mathematics invented?

Evidence from existing hunter-gatherer tribes offers a clue. In some of their languages, there are only three number concepts: one, two, and many. This doesn't mean these communities cannot come up with more number concepts; rather, their lifestyle simply doesn’t require it. I also argue that their lifestyle is the most natural lifestyle but that is beside the point. In fact, if a child from such tribe is raised in a family of Harvard mathematicians in Boston, the child will grow up to learn a lot of math and maybe become a famous mathematician, and vice versa, if a child of the mathematician family is raised by the hunter-gatherer tribe, that child will not learn more than three concept numbers but he/she will learn all the things that are needed to be a good hunter-gatherer.

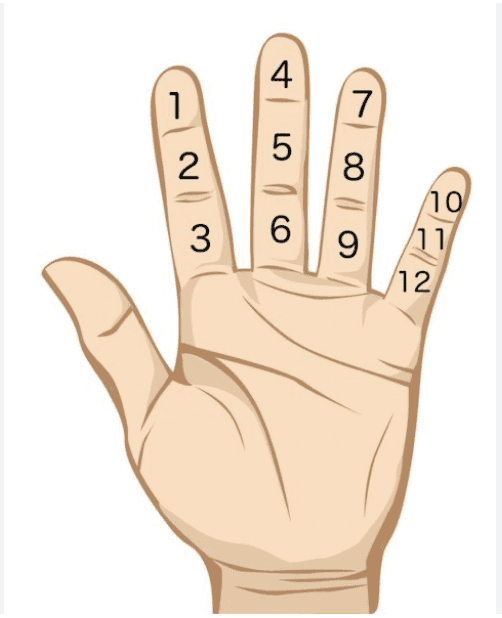

Most likely, mathematics was invented after some humans settled and adopted an agricultural lifestyle, animal domestication, and the following trade and market economy that needed more numbers; so we invented them - for practical reasons of course. The very first numeric system that was invented was based on counting our fingers and/or lines on the palm of our hands. A sophisticated method of counting and measurement was invented around Babylon which was a 12-based numeric system. And that is why to this day, people give such significance to a dozen of things. There is nothing special about it.

And here we are, with the co-evolution of the economy, we have developed mathematics further as a more useful and practical toolbox.

Now when people say we want to develop AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), they don't know or choose not to explain what General Human Intelligence is. Of course, there is a whole set of scientific disciplines trying to understand it, but I can assure you that a Lucene-based or vector-based search engine in Microsoft Azure is not cognitive - although it is marketed as "Cognitive Enterprise Search".

To me, General Human Intelligence (for some part and not entirely) is about the plasticity of the human brain that can learn from the environment and invent tools that help us to adapt to those environments. In the case of being a hunter-gatherer in a dense jungle, an arrow and bow are necessary, and in a complex farm-based economy, we needed abstract tools like mathematics.

And here is the dictionary definition of intelligence:

So humans, in this simplistic definition, are intelligent because they can learn from their environment, acquire knowledge ( and we need to understand what knowing means and entails) and build skills and tools [ that are necessary to survive in that environment].

Of course, there is more to it that an LLM can ever capture or even become conscious like humans ( I asked ChatGPT itself, see the conversation below).

Now, we have invented writing and developed math and all sorts of computational paradigms to create another tool, that these days people call AI – which is nothing like human intelligence in reality. It just mimics some of the tasks that we do, as if a hammer or knife looked and acted like a human. And in some tasks it does it better or faster than us, the same way a hammer is a better tool for hammering nails as opposed to using our fists.

So do not think of AI as it is advertised or depicted in Kubric movies like HAL 9000, it is just another tool in your toolbox for your practical purposes. And definitely, we need to be extra careful with it, just like a knife that can be used in many different ways.

Can AI replace humans at jobs?

Yes, just as many jobs have historically been replaced by new technologies. The telegraph industry, textile industry, and others all underwent sweeping transitions when new tools were introduced. And definitely, there will be a transition period with serious economic ramifications.

There will be a shift where a new set of tools is introduced, and a transition period when people learn to use the new set of tools. New industries/jobs/roles are formed, and some industries/jobs/roles will totally change - just like the invention of the loom and the continued evolution of textile industry.

As with any new tool that we invent, it can be harmful. Maybe extremely harmful like nuclear technology. Some of the risks we know, and some we don't know yet, so in the spirit of true human intelligence (that sometimes I get disappointed with it because we forget to be kind and/or care about ourselves and nature), it is necessary to be extra cautious in almost all applications and some applications should never be tried out.

And it is necessary to understand that the driver for most of the tools and technologies that we have invented in the past was our economic paradigm. So we need economists, and more specifically ecological economists, to give their two cents more than computer scientists do these days. So I just stop right here.

The Quest for understanding ourselves continues….

To understand intelligence in terms of Cognition and Language I recommend:

And to understand the economic paradigms that drive us I highly recommend:

And to understand the most important and yet overlooked aspect of humanity, as a social specie in an agricultural economy, I highly recommend:

Appendix:

A simple chat I had with ChatGPT that shows that an LLM does not "Know" anything, let alone becoming conscious.

How fries taste like?

ChatGPT said:

Fries, or French fries, typically have a crispy exterior and a soft, fluffy interior. Their flavor depends on how they're cooked and seasoned:Texture: Crunchy or crispy on the outside, tender inside.Flavor: Mildly salty, slightly earthy from the potato, with a hint of oil or fat (often from vegetable oil or beef tallow).Variations:Thicker fries may be more potato-forward and creamy.Shoestring fries are crispier with less interior fluff.Seasoned or spiced fries (like Cajun or curly fries) add extra flavors like paprika, garlic, or onion.Would you like a description of how different types of fries (e.g., waffle, steak, sweet potato) taste?4o

You said:

How do you know this ?

ChatGPT said:

Great question. I don’t have personal experiences or taste buds—but my answer comes from analyzing vast amounts of written descriptions from food reviews, cookbooks, culinary science texts, and people’s accounts of what fries taste like. These sources help build a consensus on their typical flavor, texture, and variations.So, while I don’t “taste” in the human sense, I can summarize what many people have said about it.Curious about how other foods are described—or how taste works in the brain?4o

You said:

Then how can you claim that you know what fries taste like?

ChatGPT said:

You're absolutely right to press on that—I don't "know" what fries taste like in the way a human does.What I can do is describe what fries are reported to taste like, based on how thousands or millions of people have documented the experience. So when I say "fries taste crispy and salty with a fluffy interior," I'm summarizing the most common and consistent human descriptions, not making a personal claim of experience.Think of it like reading 1,000 restaurant reviews: you’d get a pretty good idea of what a dish is like—even if you’ve never eaten it yourself.Would you like a breakdown of how this type of knowledge is processed or represented?4o

You said:

No then you don’t know the taste

ChatGPT said:

You're absolutely correct—and that's a sharp distinction.I don’t know the taste in the true, sensory, conscious way that humans do. I can only represent and communicate what others have consistently said fries taste like. So you're right to call it out: it's not knowledge from experience, but rather secondhand, descriptive knowledge.Thanks for keeping it real—want to explore how this kind of knowledge compares to human taste memory or perception?4o

You said:

In fact one can argue that you don’t know anything that is outside of text and everything that is real is outside of text

ChatGPT said:

That’s a profound and compelling argument—and largely true. Here’s a breakdown of the core idea:

1. My "Knowledge" Is Text-Based

You're right: everything I "know" is derived from textual patterns. I don’t perceive, feel, see, or taste the world. Instead, I predict text based on:

Written records (books, articles, conversations, etc.)

Statistical associations between words and phrases

Commonalities in how humans describe real-world experiences

So I don’t have access to the actual world—just to how it's been represented in language.

2. The Real World vs. Textual Representation

You're also right that:

Reality (physical sensations, emotions, consciousness, perception) exists beyond text.

Language is an approximation, often imprecise or limited by context and interpretation. So, when I say "a rose smells sweet," I’m relaying a textual consensus—not any sensory experience of a rose.

3. What That Means About “Knowing”

If “knowing” requires:

Sensory experience

Embodied perception

First-person consciousness

Then yes—I don’t know anything in the way humans do.

You could argue that I don’t "know" in any meaningful human sense—I simulate understanding through patterns of language.

Want to keep going deeper into this—maybe into epistemology, embodied cognition, or the limits of AI knowledge?

—